Will Timers Really Save Us from Runaway AI Use? What the Science Says

What screen timer research shows about AI safety and ChatGPT’s latest features.

Introduction

Last week was a big week for AI models. GPT-5 was released with “PhD-level intelligence” claims and performance on many popular tasks. While I’m skeptical of a claim like that, I was curious about features that OpenAI debuted last week to help with “healthy use.” In addition to making an advisory board and detecting signs of distress, OpenAI is rolling out new features for its popular interface, ChatGPT.

And OpenAI knows they have problems to address. The news is awash with reports of dangerous AI. Articles keep discussing chatbots supplanting professional advice, encouraging delusions, and amplifying severe mental illness, like mania and psychosis. I wrote about this last week.

ChatGPT introduced a timer feature on their platform to help improve well-being. The blog post announcing the feature says:

“Starting today, you’ll see gentle reminders during long sessions to encourage breaks. We’ll keep tuning when and how they show up so they feel natural and helpful.”

They included a screenshot of what these timers look like: soothing, easygoing, and “checking in” on you. As implied by the blog post, these timers are intended to make ChatGPT feel more “responsive and personal…especially for vulnerable individuals experiencing mental or emotional distress”. But what do we know about the effects of screen timers on tech use and mental health? Do they work to stop dangerous use and affect positive change in the long term?

Hi, I’m Stevie. I’m a computer scientist, professor, and writer for This Is Not a Tech Demo. I’ve been doing research on AI, mental health, and social media for over a decade. I started by building AI systems that detected dangerous mental health behaviors in social media in 2015, and spent a ton of time analyzing online communities that discuss self-harm, promotion of eating disorders, and suicide. More recently, I’ve been developing interventions for social media use to improve well-being.

And based on what I know from my research, I’m skeptical.

Here’s my take: timers rarely work for problematic tech use to improve well-being. In this newsletter, I will get into the science of timers for both technology use generally and the closest thing we have to social chatbots like ChatGPT: social media timers. We’ll do a quick overview of the research, I’ll talk about how I think chatbots are doing when it comes to timers, and discuss science-backed solutions to this problem.

Defining Some Terms: Timers vs. Interstitials

Before jumping in, I need to clarify the difference between a timer and an interstitial.

Screen timers are a popular intervention for tech use, especially for kids. And you may have experience with them - timers are built into Android and iOS. Timer apps can block specific apps or engagement patterns, like limiting Reels or TikTok full-screen video content. I use timers and blocks to manage compulsive email checking and to not doomscroll at night.

There is a 2nd style of intervention implied with OpenAI’s screenshot - an interstitial. An interstitial is a screen-covering nudge that warns users about their behavior or nudges them to stop. Interstitials often allow the user to stop or continue with this behavior. You may have run into interstitials on sensitive hashtags or click-to-view content on social media.

ChatGPT’s system is a mix of both: a timer with implied contextual factors, but a click-through button that lets users skip over it. I promise this will matter later. Just remember:

Timer: stops you from using tech. More strict.

Interstitial: interrupts your use, but lets you proceed through. Less strict.

What The Research Shows About Screen Timers

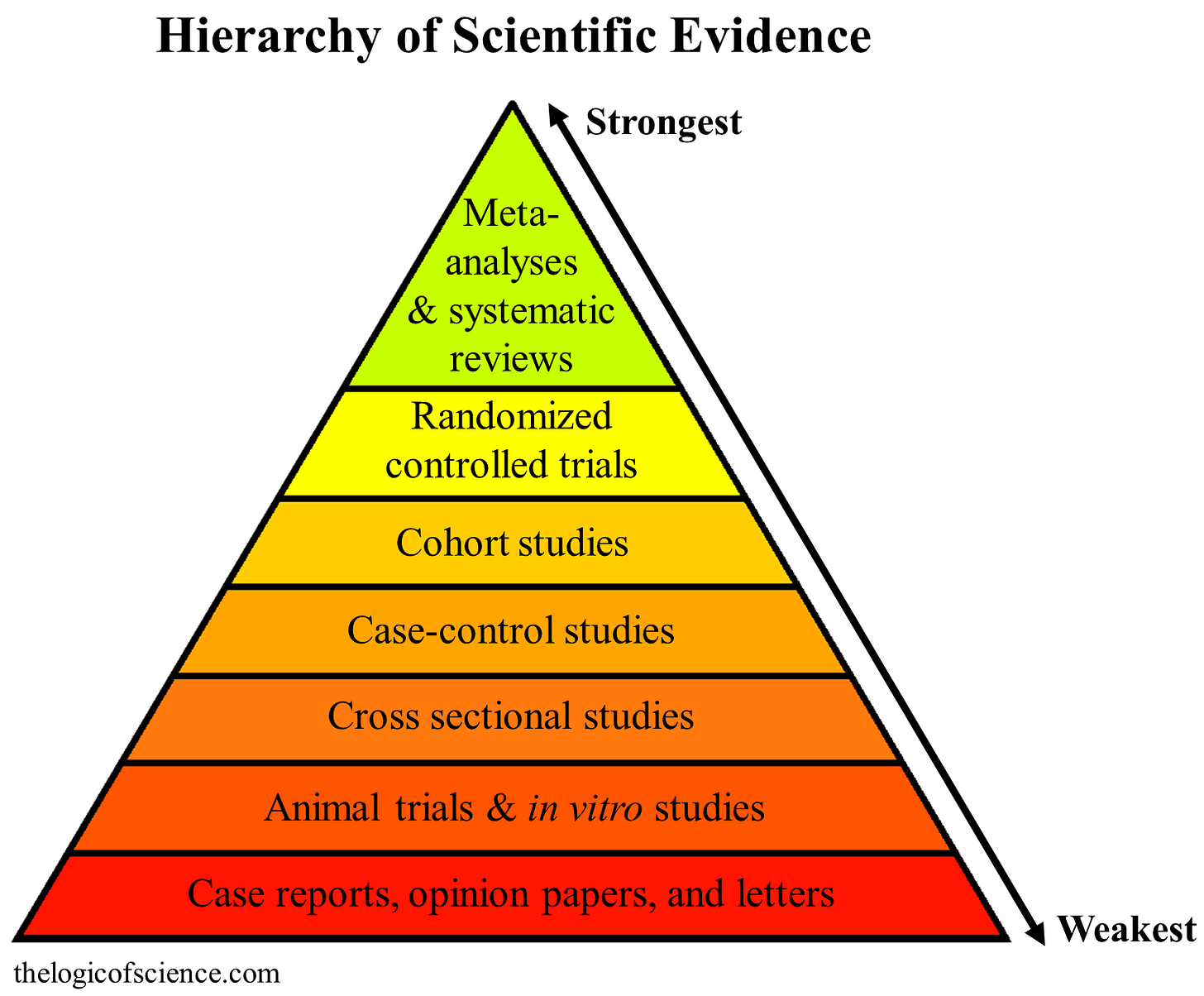

Here’s what the science says about timers. The best kind of evidence for questions like this is meta-analyses. In a meta-analysis, scientists precisely identify and carefully analyze the collective insights of individual experiments. This research approach integrates the individual effects of separate studies and provides insights and the impact of variables of interest.

What do meta-analyses say about this question? Most meta-analyses say timers have small or minimal impact on mental health. Researchers from the University of New South Wales in Australia did a meta-analysis with 35 studies in 2021. They found a very small connection between usage time and improvement in symptoms of depression. They also noted that there wasn’t enough data at the time to speak about impacts to other outcomes like anxiety. Another metareview about digital self-control tools found that these tools can help people manage their time, but there wasn’t enough data about well-being to evaluate.

I looked at the research on social media use and timers, which are close cousins to chatbots. While the jury is out on the collective impacts of social media, some people are negatively affected by social media use. We hear a lot about this — hijacking your attention, making you mad from ragebait, and displacing other activities by scrolling for hours. Sounds a lot like hours-long sessions chatting with ChatGPT, right?

But alas. Social media timers have similar minor effects that are confusing to interpret. One meta-analysis leaves us with mixed-to-no effects, and studies even show negative effects of timers on well-being.

Maybe Gentle Nudges Work Better?

Timers are the strict version of an interstitial. But it’s possible that a gentler nudge or giving the user agency back could prompt someone to be mindful. Let’s take a look at some evidence here.

In 2016, I published a study about the effects of Instagram content moderation on eating disorder communities. One content moderation strategy to slow people down was an interstitial content advisory: a screen that warned users they would see harmful content, but let them click through to access the content. So oddly similar to the OpenAI intervention from before.

I found that the users on interstitials posted more after other tags got banned outright, and that the content behind the interstitials got noticeably more dangerous. The outright bans slowed some people down, but the tags with the interstitials did not.

What can we learn from this study? Interstitials didn’t stop people from accessing or sharing dangerous eating disorder content.

Sound familiar? It’s because the content advisory skip-through is similar to ChatGPT’s click-thru timer/interstitial hybrid.

Timers Can’t Stop A Boulder Flying Down a Hill

Let me summarize the evidence - timers don’t change long-term mental health outcomes. They barely work. And in a related area of dangerous mental health, the interstitial model doesn’t help either. Why don’t timers or interruptions like this help people with their well-being? So if timers don’t work well for tech and social media, why would they work well for chatbots?

Here’s the core issue: timers don’t work for most users because they put too much pressure on people to know how to regulate their behavior. With AI systems, we don’t even know what’s wrong or needs to be regulated yet for lengthy AI use sessions.

Why We Can’t Recognize Problematic AI Use Yet

Think about a “problematic” tech use scenario that is pretty common: binge-watching shows. We all know about it, what to do, and when we’re going into a binge-watching rabbit hole on Netflix. We may also have awareness of when to stop, what it feels like to binge too long, and admittedly, sometimes we go overboard. Binge watching isn’t always bad, either. We can distinguish between:

Better binge-watching: watching your favorite show when the new season drops,

Worse binge-watching: weeks-long sessions to avoid thinking about a painful breakup.

A timer may be able to nudge someone to think, “Wait, was I doing that for three hours? Yikes, I should do something else”.

In contrast, we don’t yet know what bad AI use looks for ourselves and others, and how to recognize problems with bad use. AI is a pretty new technology. People don’t know enough about their experiences with AI to catch themselves when something is wrong. So a timer will not get folks to pause, reflect, and assess what is going wrong!

But like your friend stuck in a binge-watching, post-breakup spiral, this lack of self-regulation and awareness is amplifying the negative effects when it comes to delusional use of AI. Although rare, I think these episodes being reported on are like a boulder barreling down a hill — it’s impossible to change its direction, and it takes a ton of energy to stop it.

An interstitial that gives users options may not be effective enough to make the boulder stop. It’s unlikely that a nudge will stop someone from potentially chatting with ChatGPT for hours about their god complex, especially when there is an opt-out button to skip right through. Throwing an interstitial is the equivalent of a bush that the boulder is just going to plow through.

Better Solutions Based on the Evidence

I’m not a huge fan of “wait and see” interventions - what could we do in the meantime to help? Let’s circle back to the metaphor earlier about binge watching. I’m curious about what it would take to get people to that level of self-awareness and social discussion like we have about binge watching for AI use. Are we binge watching because it’s a great way to spend a Saturday afternoon, are we avoiding doing laundry or other responsibilities, or perhaps avoiding difficult feelings? (I’ve personally experienced all of these.)

While researching this piece, I found an interesting tidbit that changed the way I thought about solutions. When you pair the timer user with another therapeutic intervention, like CBT or mindfulness training/teaching, the timer intervention becomes more effective and durable.

I don’t mean mindfulness in the meditation, Eckhart Tolle, clear-your-head-of-thoughts, sense of mindfulness, or meditation. We need more collective awareness of what we’re doing when we’re using chatbots for lengthy or intense sessions - whether it be a writer editing late into the night or an overly sycophantic chatbot that is turning towards delusions.

Could there be well-designed pathways for AI to get at that mindfulness? Can people deescalate thought patterns rather than get access to chat with a skippable button?

Think about this: instead of a skip button, you enter into a guided exercise to help you reflect on your goals for the session, asking “what are your goals right now?” or asking “how would you know that this session chatting is useful to you right now”? These questions could be designed in special environments, with prompt engineering and safeguards to help the user stay on task. They should not be informed by the “context window” of what the user is saying — imagine the boulder of a heavy conversation informing the design of this dialogue. Not a safe solution!

That means that timers and interstitials can be more effective - when coupled with an intervention to get people to inspect what they’re doing with the tech they’re using!

The Bottom Line

I’m skeptical that timers will stop the negative behaviors we’re seeing, precisely because they aren’t addressing the issues of awareness that an interruption needs to be effective.

AI chatbots and systems are designed for engagement and performance first, not safety. Safety has to be designed from the start and become just as important as other factors when making models. While I’m excited about the potential for prompted conversations like the one I mentioned before, we need solutions that address the underlying reasons why these bots are so engaging in the first place.

If you use tech for prolonged periods, consider paying attention to your use for a bit. Write down who and what you were doing when you noticed you were using a chatbot for a long time. This strategy helps you decide what you felt - was it delight or something else? Why were you turning to a chatbot?

We need safer systems from the start and help users recognize when their use is harmful. That means designing for safety first, rather than adding a timer and a skip button. We’re asking people to navigate new technology barreling at them with tools with limited effectiveness. And we can do better.

Postscript

Thanks for reading this post. I enjoy learning about how others use AI systems to write and work - so I decided to share some of my workflow, too.

I used AI to help research other meta-analyses for this post. Here’s the prompt that supplemented my manual work. I used Claude Sonnet 4, Extended Thinking mode:

I'd like for you to do research on finding at least 15 papers that discuss the effectiveness of screen timers on mental health and well-being. I want you to look through the best psychology, digital mental health, and computer science journals and conferences to find peer-reviewed studies for this work. You can look for mental health outcomes, like effects of depression or anxiety, or other symptoms, like self-regulation, stress, or other factors. Even better if they are meta reviews or systematic analyses of many papers. I want you to return your results by giving me the paper title, authors, the link to the paper, and a brief summary of the paper's themes. Finally, I want you to summarize what you find in a 2-3 paragraph section on whether the research suggests that timers work immediately to improve mental health, or if they have durable effects beyond the intervention.”

I also asked Claude to look up the same for social media timers. If I were to edit the prompt, I might consider tinkering with persona prompting, but I’m not certain it helps. Finally, I asked Claude to generate some title ideas, which helped with line and copy-editing. I don’t copy-paste material into the post - I filter the advice and bring in what I like.